Judith Hewitt, co-manager of the Museum writes...

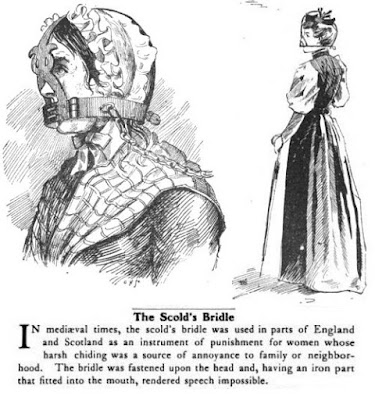

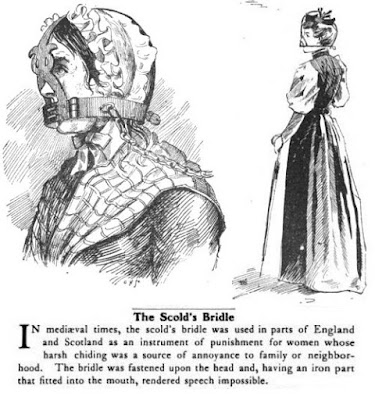

Recently, the Museum was approached by the Travel Channel to appear on their Mysteries of the Museum programme. They wanted to focus on one specific case that of Jane Wenham in 1712 and on one specific object - the Scold's Bridle. As part of my preparation for this interview (which lasted three hours!) I researched the Scold's Bridle in detail and this research forms the basis of this month's object of the month.

The Museum has two scold's bridles in its collection (object numbers 161 and 162). Object number 162 is said to have come from Exeter Castle.

The founder of the Museum, Cecil Williamson, wrote of it:

"A

so-called scold's bridle, but in actual fact this bridle is reported to have

come from Exeter castle where it was kept to clap on any female prisoner who

gave way to shouting, swearing or screaming abuse during the night hours, it is

highly uncomfortable to wear, for discomfort is the name of the game." and "The

purpose of the bridle was to prevent the witch shouting and cursing the town or

persons in authority."

It is said that the earliest reference to a bridle worn by a woman is made in the 1380s by Geoffrey Chaucer who has one of his characters say:

“But for my daughter Julian

I would she were bolted with a Bridle

That leaves her work to play the clak

And lets her Wheel stand idle.”

Allegorically, the figure of Temperance is often shown with a bridle. The bridle was said to represent a control of all the appetites, not specifically the control of the tongue.

Above: Temperance with a Bridle (after Raphael) by Samuel Woodforde

The scold's bridle was never a national legal punishment endorsed by legislation. It was a local measure adopted in some areas but not used in other (women in Derbyshire, for example, were said to be so calm and such good wives that the scold's bridle was never needed there!). It was a humiliating punishment and could function as a method of torture in some cases. The scold's bridle in the past was more commonly referred to as the branks. The reasons for this name are unclear but it may derive some lost North European or Viking expression. One other theory is that it derives from the Old French "bernac" for barnacle (which was an instrument put on a horse's nose to keep it quiet).

Most people assume the bridle was only ever used on women as “Scolding women in the olden times were treated as offenders against the public peace…” but the earliest documented examples of its use in Britain refer to its use on any person of guilty of the specific crime of blasphemy (a law from Edinburgh in 1560 stated that all persons guilty of blasphemy should be punished by the iron brank) or the more general crime of immorality. On 7th October 1560, David Persoun of Canongate, Edinburgh was found guilty of fornication and forced to “be brankit for four houres” The woman he fornicated with was banished from the city!

Later examples of its use give clues as to why it is sometimes called

"the scolds or gossip's bridle". In 1574, records from Glasgow record the punishment:

“two scauldes to be branket.” In 1600, the

"brankes" is mentioned in Stirling as punishment for a shrew. In 1699, Cecily Pewsill

“a notorious scold in the workhouse” had to wear the branks in the street for half an hour. In 1741, Elizabeth, wife of George Holborn in Northumberland was tied to the market-cross for two hours for

“scandalous and opprobrious language to several people.” In 1789, the branks was used in Lichfield. A local farmer enclosed a woman’s head

“to silence her clamorous Tongue” and led her round a field while boys and girls

“hooted at her” “Nobody pitied her because she was very much disliked by her neighbours.”

The bridle was often used as part of a public display and is similar in intention to the ducking stool - the aim was to humiliate the "offender" before their community and to titillate the spectators,

“such a bridle as not only quite deprives them of speech, but brings shame for the transgression, and humility thereupon.”

The earliest known reference to the bridle in England comes from Macclesfield. In the town records mention is made of “ a bridle for a curste queane” assumed to be prostitutes or women or “lighte behaviour and loose morals.”

An interesting case from 1655 sheds some light on the use of the bridle to silence women as well as religious dissent. Quaker women in Carlisle, “…were led through the Street with each an Iron Instrument of Torture call’d a Bridle on their Heads to prevent their speaking the Truth to the People. Having been so expos’d to the Scorne and Derision of the Rablle they were turn’s out of the City.”

Some call the bridle the witch's bridle and associate it primarily with that time of misogyny and persecution: the Witch Trials. While there are cases of the bridle being used on accused witches who were later executed, there are far more examples of its use as a general punishment for scolds (for whom this was probably the only punishment). To historian James Sharpe, these are two facets of the same intolerance as he refers to "The witch and her sister the scold." Part of the cultural idea that noisy, quarrelsome women were dangerous. There was a genuine fear of female conspiracy and the power of female words in the early modern period. Doctor Johnson probably spoke the view of the majority when he said “I am very fond of ladies, I like their beauty, I like their delicacy, and I like their silence.” The ideal of the quiet woman can be found in 18th century ballads such as this one:

“A woman should like echo true

Speak but when she’s spoken to

But not like echo still be heard

Contending for the final word.”

One of the theories of the persecution of witches at this time is that they were intelligent women who would not be silenced,

“Deprived of virtually all political influence the woman was left with one weapon of freedom her tongue, the liberal use of which branded her a “scould” possessed of unwomanly aggressiveness.”

And so we come to the bridle and witchcraft accusations. One particularly gruesome account was that of Agnes Sampson,

who was examined by King James himself at his palace of Holyrood Palace in 1590. She was

fastened to the wall of her cell by a “witch's bridle” an iron instrument with

four sharp prongs forced into the mouth, so that two prongs pressed against the

tongue, and the two others against the cheeks. She was kept without sleep,

thrown with a rope around her head, and only after these ordeals did Agnes

Sampson confess to the fifty-three indictments against her. She was finally

strangled and burned as a witch.

In 1661 we find a reference to “The Bridle with which the wretched victims of superstition were led to execution.” in Forfar in Scotland. In 1676 there is a reference in West Yorkshire to the “scolds brank”

made of iron “with an iron gag that fitted into the mouth” The records indicate that it could be fitted with

a spiked collar when used on alleged witches.

There are many examples of the use of the bridle after the end of the period of intense persecution of alleged witches. In 1799, it was used on an imprisoned murderer in Nottingham to keep him quiet in his cell while he awaited his execution. These branks were nicknamed "The Iron Gag". In 1807, the branks were publicly displayed in the police court at Shrewsbury as a deterrent. In 1876, a magistrate silenced arguing women in his court by pointing to the branks hanging on the wall of the Newcastle courtroom. Branks could be found hanging outside the office of the Mayor in some towns as a warning and deterrent.

According to one account, in Chester, “In the old…houses of the borough, there was generally fixed on one side of the large open fire-places a hook, so that, when a man’s wife indulged her scolding propensities, the husband sent for the town jailor to bring the bridle, and had her bridled and chained to the hook until she promised to behave herself better in future…I…have heard husbands say to their wives “If you don’t rest your tongue I’ll send for the bridle and hook you up.”

By 1900, there were an estimated 33 branks still in existence in Britain. Their use had gradually diminished as the Victorians eradicated punishments which they saw as old fashioned, irrational and too boisterous. In 1821 a Nottingham ordered for the branks there to be destroyed, saying only

“Take

away that relic of barbarism.” By the end of the 19th century, women had more legal rights than before and this punishment seemed outdated. Interestingly, it is at this time that many Victorian collectors began to collect and create reproductions of the branks and to write books on "bygone" punishments congratulating themselves on their modernity while at the same time exhibiting a voyeuristic and fetishized interest in the punishments of women in the past.

References

All information in this article derived from the following texts in the Museum library:

James Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness (1996)

William Andrews, Bygone Punishments (1899)

E.J. Burford & Sandra Shulman, Of Bridles & Burnings, The Punishment of Women (1992)